12 Songs By African-Americans That Shaped The 20th Century And Made White America More Progressive | Critical Analysis |Axisoflogic.com

|

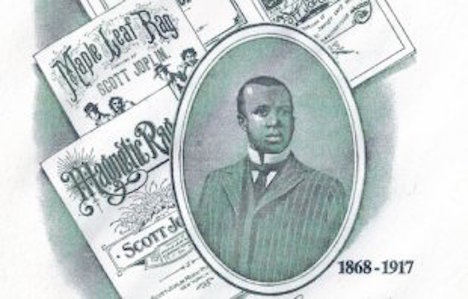

| Scott Joplin. Photo Credit: U.S. Postal Service |

For more than a century, white Americans have been drawing on black American culture and the country has been better off for it. Whether or not today’s largely white governing class will act on the racial injustices raised by nationwide protests on abusive policing is an open question.

But the pattern of white America listening and learning from communities of color is unmistakable—and goes back further than most people think. My new book, On Highway 61: Music, Race And Cultural Freedom, traces this narrative and the roots of American counterculture from its earliest days, and especially through the intersection of music and civil rights.

What follows are 12 songs from the late nineteenth century through the 1960s civil rights movement that mark how white America became more progressive by listening to African-Americans.

1. Maple Leaf Rag – Scott Joplin, 1899: Late in the 19th century, the first generation of African-Americans born after Emancipation came of age. One result was an extraordinary burst of creativity, largely in music. Ragtime was the earliest example to affect the white majority, and its finest flower was Scott Joplin’s 1898 “Maple Leaf Rag,” widely thought to be the first million-selling (sheet music) song.

The real impact of ragtime, the one that would appall and even terrify the guardians of civic morality – to quote Meredith Willson’s “The Music Man”: “Libertine men and scarlet women and ragtime / Shameless music that’ll grab your son, your daughter / into the arms of a jungle animal instinct… Ya Got Trouble” – came in 1912, when dancing to ragtime swept the country.

2. Alexander’s Ragtime Band – Irving Berlin, 1911: There was a block on 28th St. in Manhattan that contained some twenty-one music-publishing firms, each with someone pounding on a piano while writing tunes. When summer heat made for open windows, the resulting cacophony earned it to the label of “Tin Pan Alley,” and it remained the heart of American popular music from the turn of the century until the 1960s, when Bob Dylan ended its reign.

Its quintessential early star was Isidore Balleen, Irving Berlin, who would earn the sobriquet “King of Ragtime” with “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” which did indeed have some ragtime elements and pleasantly lacked the other attributes most of the white-written rags included, like “coons.”

3. St. Louis Blues – W.C. Handy, 1915: Though there is no way to verify it, it seems quite likely that the blues emerged in the 1880s and 1890s in Mississippi, and with remarkable swiftness were being played from Texas to South Carolina not long after. The songs were highly variable, and featured what was called “floating verses,” in which different fragments of lyric slid from song to song. There were a lot of songs with “the sun is gonna shine on my backdoor some day…”

At the turn of the century, a classically trained musician named William Christopher Handy heard the blues – although the players called them reels – being played at a Mississippi train stop, and eventually translated them into songs, first the “Memphis Blues” and then his masterpiece, “St. Louis Blues.” He was not, as his autobiography put it, “Father of the Blues,” but a bridge between the rural black folk world of the earliest blues and the white world of sheet music and copyrights. And it’s a beautiful song.

4. Livery Stable Blues – Original Dixieland Jazz Band, 1917:Black music would unsurprisingly enter the wider (white) world through the playing of white people. Actually “Livery Stable Blues” is neither a blues nor jazz, but a vaudeville song that featured novelty sounds like the neighing of a horse. But it was fast and peppy and sold a million copies, thus introducing the idea, if not the reality, of jazz into the national American conversation.

5. Crazy Blues – Mamie Smith, 1920: To this point, such blues songs as had been recorded were the work of white vocalists. Finally, a Broadway hustler named Perry Bradford convinced the music director of the OKeh label, Fred Hager, to consider recording a black woman named Mamie Smith. The first pass was with a white studio band and was sufficiently popular that they returned to the studio. This time, Bradford persuaded Hager to use a black band, “the Jazz Hounds,” which included the great stride pianist Willy “The Lion” Smith.

“Crazy Blues” was not great and not even a blues, but a vaudeville lament that proceeded to sell more than a million copies, which had several consequences: one was that the record companies woke up to the fact that black people bought records. As a result, the hunt for other black women vocalists assumed high priority (black men emoting was thought risky in these racially charged times).

6. Backwater Blues – Bessie Smith, 1927: One of the beneficiaries of the new record company policy would also turn out to be one of the great American voices of all time. Bessie Smith had, wrote Eddie Condon, “timing, resonance, volume, pitch, control, timbre, power – throw in the book and burn it; Bessie had everything.” She could also write songs.

The great Mississippi flood of 1927 generated at least two masterpieces – Charlie Patton’s “High Water Everywhere” and Bessie’s “Backwater Blues.” Touring in Cincinnati, Bessie witnessed the edge of the flood – the epicenter was in Mississippi – and went into the studio in New York to record it accompanied only by the master of stride piano, James P. Johnson.

7. West End Blues – Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines, 1928: Jazz had brought together ragtime syncopation, the blues, and European instruments in New Orleans at the turn of the century, and within twenty years it had become a subtle and sophisticated art. Born at the same time as jazz, Louis Armstrong was destined to take it to the next level. Though mostly playing in large orchestras, the fashion of the era, he created indelible art by assembling small (the “Hot 5,” the “Hot 7,”) studio groups and redefining jazz as the soloists’ art. Working with one of the few musicians of the era who could be considered his peer, Louis and Hines fashioned in “West End Blues” the high-water mark of early jazz.

8. Blue Yodel #9 – Jimmie Rogers with Louis Armstrong and Lil Hardin, 1930: The notion that there was such a thing as purely “white” music was flawed at least from the time that black singing began to affect all of American protestant church music after the Great Awakening of the 1740s. The Carter Family, “the First Family of Country Music,” hunted songs with Lesley Riddle, a black man. The banjo was an African instrument. Et cetera.

Jimmie Rodgers, the “Father of Country Music,” not only yodeled – almost certainly borrowed from black railroad workers, “gandy dancers” – but reached out to record his masterpiece, “Blue Yodel #9,” with Louis Armstrong and Lil Hardin, one of the early and very important black-white collaborations.

9. King Porter Stomp – Benny Goodman, arr. By Fletcher Henderson, 1935: Musical white youth in Chicago in the 1920s had an extraordinary opportunity to listen to the masters of the new art of jazz. There was a particular group who attended Austin High School in the suburbs – and became known as the Austin High Gang – but they were joined by friends like drummers Dave Tough and Gene Krupa, pianist Jess Stacey, and the brilliant clarinetist Benny Goodman.

To this point, jazz had been defined as either sweet (Paul Whiteman, Guy Lombardo) or hot (black). These youngsters preferred hot, and by the 1930s, called Swing (supposedly the BBC found the phrase “hot jazz” offensive), they took over American popular music. The “King Porter Stomp,” written by Jelly Roll Morton and arranged by Fletcher Henderson, is perhaps the classic example of the early meeting of black and white in the universe of jazz.

10. Now’s the Time – Charlie Parker, 1945: Black music was so vital that by the time of World War II it trifurcated. The rural blues would add electricity and become the electric/Chicago blues. One segment of big band jazz would become urban party music, “Rhythm and Blues.” And one part of jazz would become art music; they called it bebop, bop for short. It was virtuosic, complex, and revolutionary in terms of its approach to rhythm and harmony. Socially, it reflected the era in its refusal to pander to overt entertainment values. It was a new dawn.

11. Shake, Rattle and Roll – Bill Haley and the Comets, 1955: Bill Haley was a country-western Disc Jockey whose time was followed by an R & B show. He liked the show’s theme song, “Rock the Joint,” and began to play it in his band. Soon he was being tutored in the finer points of Louis Jordan’s R & B shuffle rhythm, and a musical marriage of sorts gave birth to rock ‘n’ roll. “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” a sizeable hit for Big Joe Turner, now became a gigantic hit, and once again white kids danced to black music played by white guys.

12. Blowin’ in the Wind – Bob Dylan, 1962: Bob Dylan had grown up listening to black music on Gatemouth Page’s “No Name Jive” radio show from Arkansas, patterned his earliest high school bands after Little Richard, and studied Lead Belly and Odetta before he adopted his son-of-Woody Guthrie persona. Then he fell in love with a CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) volunteer just six weeks after the Freedom Rides, the shining example of a brave moral crusade in 20th century America. The result was an anthem called “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which connects musically with “Many Thousands Gone,” a spiritual sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers, the first black musicians to tour the North. Both songs influenced white people for the better.

A Two-Way Street

There have also been examples where white American artists whose work built on the long legacy of African-Americans inspired black artists to be more bold and forthcoming. The best example is Sam Cooke’s heartfelt prayer expressed in song, 1964’s A Change is Gonna Come.

Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” had a number of effects, one of which was to convince the great Sam Cooke that he could write a song of social impact and still be part of the pop music world. The result was his masterpiece. After all the borrowing from black music by white people, the circle came full.

Dennis McNally is a cultural historian and author with an interest in Americans who challenged conventional mainstream thinking.

Source URL