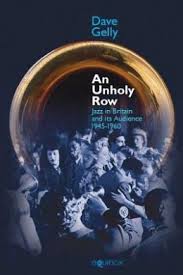

An Unholy Row – Jazz in Britain and its Audience 1945-1960

BY PETER BACON on 23 JUNE 2014 •

By Dave Gelly

(Equinox, hb, 167pp, £25.00)

Review by Peter Vacher

Two things to say straightaway and interests to declare. First, I know author Gelly quite well and second, I supplied eight images from my jazz photo collection for his book. That said it may be pertinent to remind Jazz Breakfast readers of Gelly’s credentials before we talk about the book.

He is, and has been for many years, the jazz correspondent of theObserver newspaper, has written perceptive biographies of his heroes, Stan Getz and Lester Young (the latter also published by Equinox) and of even greater moment plays jazz tenor saxophone professionally and well. Born in 1938, Gelly embraced jazz and began to play during the very period which the book covers. So his is a commentary informed as much by first-hand knowledge as it is by his extensive research.

He is, and has been for many years, the jazz correspondent of theObserver newspaper, has written perceptive biographies of his heroes, Stan Getz and Lester Young (the latter also published by Equinox) and of even greater moment plays jazz tenor saxophone professionally and well. Born in 1938, Gelly embraced jazz and began to play during the very period which the book covers. So his is a commentary informed as much by first-hand knowledge as it is by his extensive research.

The subtitle suggests something more than a strictly chronological account of jazz in Britain during the cited decade and a half and that is what Gelly delivers here. He’s good at capturing the mores of the times, as Britain moved from a war-time economy to the first awakening of the ‘never-had-it-so-good 1960s’.

This was when jazz found an audience among the young, newly-liberated from the stifling conventions that had marked their parents’ lives, sometimes to their senior’s despair, hence the title of the book. He’s even-handed about styles, understanding the sincerity of the early revivalists and tracing the rise and rise of traditional jazz and skiffle before moving over to consider the passionate espousal of the modern style promoted by the collective known as Club Eleven and the more aware dance band players of the day.

He rightly emphasises the role played by the open-minded Humphrey Lyttelton and John Dankworth, two men who largely shook off their early American influences as they sought to produce distinctive music of their own. There’s social history here but it’s British jazz history too, neatly caught and clearly expressed. No fuss, no over-elaboration, all appropriate quotations included, the whole a perfect reminder for this observer of a time when the discovery of jazz seemed, in Eddie Condon’s immortal words when describing Bix Beiderbecke’s playing, like “a girl saying yes”.

The typos are few although failing to spot the mis-captioning of drummer Bobby Orr as ‘Booby’ in Val Wilmer’s photo [p.122] is unforgiveable. The picture choices are excellent (I would say that, wouldn’t I?) while the accompanying Notes, Bibliography and Guide to Recordings add real value. Sadly, the indexing doesn’t. Don’t let these minor cavils put you off – Gelly’s book is literate, lightly done but meaty all the way through.

History for jazz people, you could say.

© Peter Vacher