|

https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/03/opinions/bill-withers-ellis-marsalis-music-world-covid-19-losses-seymour/index.html

Covid-19 is ravaging the music world

Gene Seymour is a film critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post. Follow him on Twitter @GeneSeymour. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion at CNN.

(CNN) — A dispiriting couple of weeks in the lives of music fans have now climaxed with the death of Bill Withers, whose lean, leathery-tough vocals on such pop classics as "Ain't No Sunshine," "Use Me," "Just the Two of Us" and "Lean on Me" were deeply woven into the soundtracks of several generations' lives.

Withers died Monday at 81 of what his family has described as "heart complications." His death has not been linked to the Covid-19 virus. But his loss, coming at about the same time that "Lean on Me" has resurfaced as a global anthem of collective will during the coronavirus pandemic, nonetheless feels like another in an already seemingly relentless series of recent body blows to the music world.

Among the casualties: Adam Schlesinger, Fountains of Wayne founding member, lead vocalist and songwriter; Joe Diffie, Grammy-winning country-music singer; Alan Merrill, best known for writing Joan Jett's 1980s anthem, "I Love Rock and Roll;" Manu Dibango, a Cameroon saxophonist whose riffs on the hit 1972 dance tune, "Soul Makossa," helped spearhead worldwide interest in African pop; and Aurlus Mabelle, the Congolese song-and-dance man dubbed king of the eclectic blend of black pop genres known as "soukous."

Of all music genres, however, it is jazz that's been struck especially hard and deep by Covid-19. Four musicians of varied ages have died in the last few weeks from the disease, the most recent of which are Ellis Marsalis and Bucky Pizzarelli, two master instrumentalists who found widespread fame relatively late in their storied careers and also passed their legacies on to their children.

Marsalis, who was 85, was a fixture in his native New Orleans as a pianist doggedly advancing the cause of bop and other post-1940s jazz music in a city more inclined to embrace the pre-swing era of the 1920s. Over time, Marsalis' commitment, chops and reputation as a music educator won him respect and affection from the musical cognoscenti of his hometown.

Of Marsalis' many prominent students, including Terrence Blanchard and Harry Connick Jr., the most celebrated were four of his six sons. The achievements of Branford, Wynton, Delfeayo and Jason Marsalis were considerable enough to transform the Marsalises into the unofficial royal family of jazz. Along with their dad, they also were staunch and at times acerbic defenders of jazz tradition which by the time Branford and Wynton became breakout stars in the early 1980s, also encompassed the kind of hard bop music their father continued to play into his 70s and 80s.

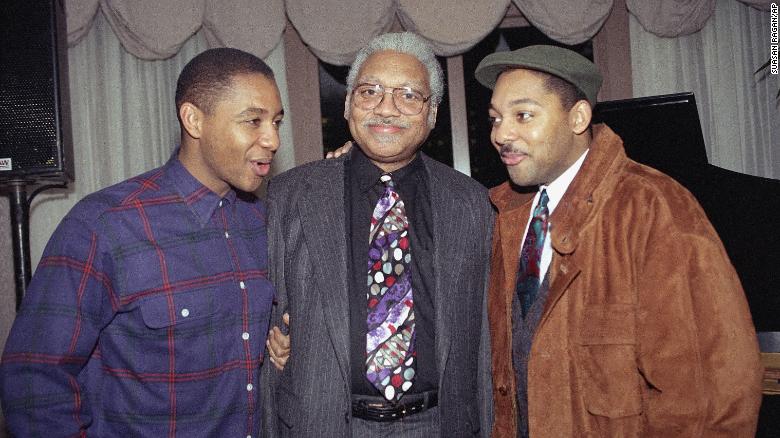

Ellis Marsalis is joined by two of his sons, Branford (left) and Wynton.

Bucky Pizzarelli, who died at 94, was a buoyantly lyrical guitarist who spent most of his early career as a session musician working in recording studios and with such bands as Benny Goodman's and the Tonight Show's NBC Orchestra. He became a fixture in New York nightclubs, playing in several small ensembles with such musicians as saxophonists Zoot Sims and Bud Freeman and violinists Joe Venuti and Stephane Grappelli.

Most noteworthy of these professional affiliations was the one he shared with his son John, whose performances with his father, beginning in 1980 when John was 20, were also a kind of apprenticeship, enabling eventual renown in his own right as a guitarist and singer. Indeed, John Pizzarelli's fame reached the point that his dad proudly and happily played a supporting role in his son's own high-profile gigs.

What made the deaths of these two father figures in jazz especially poignant was that they continued to play, teach and inspire deep into their senior years with the possibility of having even more to contribute to the music through the growth of their students.

Pianist Mike Longo, whose coronavirus-related death at 83 came March 22, was, along with Marsalis, a pianist and educator of comparable gifts and influence. His glittering resumé, including providing backup to saxophonist Coleman Hawkins and singer Nancy Wilson (among others), is dominated by his longtime association with trumpet great Dizzy Gillespie, who tapped him to be his musical director and arranger in 1966 and continued to work with him, formally and informally, until Gillespie's death in 1992.

Besides his work as a writer, arranger and teacher, Longo directed the New York State of the Art Jazz Ensemble, which he founded in 1998. He continued to perform music until almost the end of his life.

Wallace Roney's death this past week at 59, hit the global jazz family especially hard because it came as he was building upon an already formidable reputation as a trumpeter, bandleader and composer. Along with Marsalis' two elder sons, Branford and Wynton, Roney was considered a prominent member of the so-called "young lions" at or near their 20s in the 1980s who were out to retrieve acoustic jazz music's once prominent place in the American mainstream.

With his smoky blue tone, slippery timing and cagey dynamics, Roney was perceived at the outset as little more than a Miles Davis clone. Indeed, the usually truculent Davis enthusiastically declared Roney his protégé. Those listening closer, however, would hear other influences, from Clark Terry to Freddie Hubbard, filtering through Roney's playing. Over decades, Roney's voice would achieve a gritty agility and pensive romanticism that belonged to him and him alone. His intelligent and at times startling negotiations between jazz's past and present implied a future of greater glories — now shockingly, painfully made inaccessible by pandemic.

No one knows how long this coronavirus siege will last, or who else we may lose. But one can hope that the spaces left open by these musicians' deaths will be occupied over time not only with fresh new voices, but with a wider, deeper appreciation of how jazz nurtures and nourishes many lives at once — maybe even your own, if you let it.

|