The Coltrane Home in Dix Hills

By Andy Battaglia

The deceptively ordinary house where Coltrane composed A Love Supreme.

Coltrane’s unassuming house in Dix Hills.

In an empty corner of a modest home in suburban New York, hiding beneath a construction zone’s deposits of dirt and dust on the floor, is a patch of bright, bold, almost electrically colorful vintage purple carpet. It couldn’t be more out of place; the rest of the surroundings are just exposed old wall beams and tattered bits of plaster coming down. But it seems right at home, somehow calm and calming, in the midst of it all.

The carpet dates back to the 1960s, when John and Alice Coltrane used to live here and make their way back to the same corner room to go to sleep at night. Close by the master bedroom was the kitchen, the heart of the home in a way, and from there the hallways led out to the kids’ rooms, the den with the fireplace, and the garage out to the side. Over that was the ashram. In the basement was a recording studio. Then, up a now tenuous set of stairs, was the chamber that made this modest suburban home most famous: the room where John Coltrane composed his stirring, searching masterwork A Love Supreme.

The house itself was not especially famous, nor even really known for the better part of the past three decades. After John died, in 1967, Alice Coltrane continued living and working there before venturing out to California in the early ’70s. Other tenants took it over, none intensely invested in the heritage of jazz. A woman who knew Alice around town lived there for about a decade and then sold it to another who used it mostly as a rental property. Then it went abandoned, for years, while awaiting demolition by a developer who could make more money by flattening the house and turning over the land.

Now, ages after the Coltranes moved there in 1964, the decay has stopped and started to swing back around. Walls are going up instead of down, and graffiti sprayed by vandals on the fireplace—below the display shelf where John kept a copy of A Love Supreme on show—will be removed. The Coltrane Home in Dix Hills, as the house is now known, is on its way to becoming a museum soon. Or at least that’s the plan.

The trip out to Dix Hills is an hour ride on a commuter train from New York City and twenty minutes more from the station, down a street that is aggressively plain. Suburbs in America don’t get much more suburban than the suburbs in Long Island. Levittown, the first concerted suburban development project and the model in many ways for American expansion in the boom after World War II, is just a half hour away. Other parts of Long Island became a haven for mid-century modernist architecture and design, including some by founders of the Bauhaus. But otherwise, in the past as in the present, there could be little to take in except for houses and yards, houses and yards, and even more houses and yards.

The Coltranes moved here from Saint Albans, Queens, an area in the city that was itself a long way away from all the manic Manhattan action. But still: it’s hard to fathom the change. They lived quietly on Long Island with kids, including Ravi Coltrane, who makes his way as a jazz saxophonist today. He was born there and spent his earliest years in the house in Dix Hills. He dabbled as children do in the “playroom,” which is what they later called the place upstairs where his father went to work on his grandest album. It’s tempting to imagine it now as a lair, a solemn space, sacrosanct. But the reality was likely different.

“At the moment of conception, every great human gesture took equal standing among the details and demands of daily life,” writes Ashley Kahn in the liner notes for a latter-day deluxe edition of A Love Supreme. “While creating his most ageless canvases, Picasso stepped back and swept the studio. While developing their masterpieces, Beethoven paid the bills, James Joyce lit out for the bar, and Louis Armstrong took five and grabbed lunch.

“For John Coltrane in 1964,” he continues, “inspiration coincided with dirty plates and diapers.”

The inspiration was evidently intense, whatever its milieu. As Alice Coltrane recounts in Kahn’s full-length book on the subject, A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album, “There was an unoccupied area up there where we hardly ever went … John would go up there, take little portions of food every now and then, spending time pondering over the music he heard within himself.”

After a particularly heady five-day spell, he descended: “It was like Moses coming down from the mountain, it was so beautiful. He walked down and there was that joy, that peace in his face, tranquility.”

The room now is a shambles. All that’s left is rotten wood and tacky floral wallpaper added long after the momentous setting’s prime. The view is the same, though, out into a backyard thick with trees. It’s disquieting to stand and look out over what John Coltrane would have seen—did see—in whatever state of mind he found himself gracing when in the throes of A Love Supreme. Some of the material on the album had origins going back to live performances from earlier on, but in the little room with the windows upstairs is where he supposedly struck upon the album’s arrangement as a whole. “Acknowledgement”—“Resolution”—“Pursuance”—“Psalm”: it would be hard to come up with a more resounding series of musical creations, in jazz or otherwise, and the room where it all happened can be accessed still.

The view from the room where A Love Supreme was composed.

Layers of peeling wallpaper and paint.

Making that access more open and appealing is part of a project that has been ongoing since 2004. That is when Steve Fulgoni, a local business owner in Dix Hills who is also a voracious jazz fan, broke his way into the house to take a look around. Knowledge of the Coltranes having lived in the area had spread among devotees, but the address wasn’t known, in part because of a misleading mention in a biography. When Fulgoni tracked down an old delivery boy who remembered the jazz legends as neighbors, he found the house as it had been described, simple and unassuming behind a rusting iron gate. To his shock, it was abandoned—an incongruous suburban ruin.

He started petitioning the town of Dix Hills to save the historic home at once, but he had never been inside to see exactly what was there. So he went, with a friend, at night.

“We were trespassing. We had flashlights,” Fulgoni said. “It was scary. We could tell there were raccoons. But inside, I immediately felt something special, a presence of some sort.”

He went down to the basement and saw the remnants of the recording studio, which Alice completed after John’s death and used to record albums of her own including Monastic Trio and Journey in Satchidananda. He ventured into the meditation room, which Alice ran as an ashram for a spell.

“I saw the shag rugs and could tell this was all from a different time,” Fulgoni said. “There was a piece of paper in the corner, a newspaper that happened to be from the anniversary date of John’s death. I looked at that and started to tremble. That’s when I left and said I need to do something … ”

The house’s unceremonious recent past had proved a blessing. With many of its years designated as a rental to young tenants and indifferent college kids, little of the original decor had changed. Dated wood paneling that lined a main wall in the living room remained. The ashram’s shag carpeting, arranged in the vibrant colors of the chakras, went untouched. And the bright purple carpeting in the bedroom, in a hue associated with wisdom, transcendence, and universality, looked as if it could have been laid down days before.

The structure, however, was a mess. After Fulgoni convinced the town of Dix Hills to buy the house and repurpose it as a historic site, work turned to tearing much of the inside down. Water damage had set in in drastic fashion, and infestations of mold made it unsafe. Other problems that attend a house left in utter neglect for years abounded.

“We’ve stabilized it—it’s not getting any worse,” said Ron Stein, president of the Coltrane Home, on a recent visit there. “Now the goal is to really move forward with the renovation in a significant way.”

Coltrane in 1963. Photo: Hugo van Gelderen / Anefo

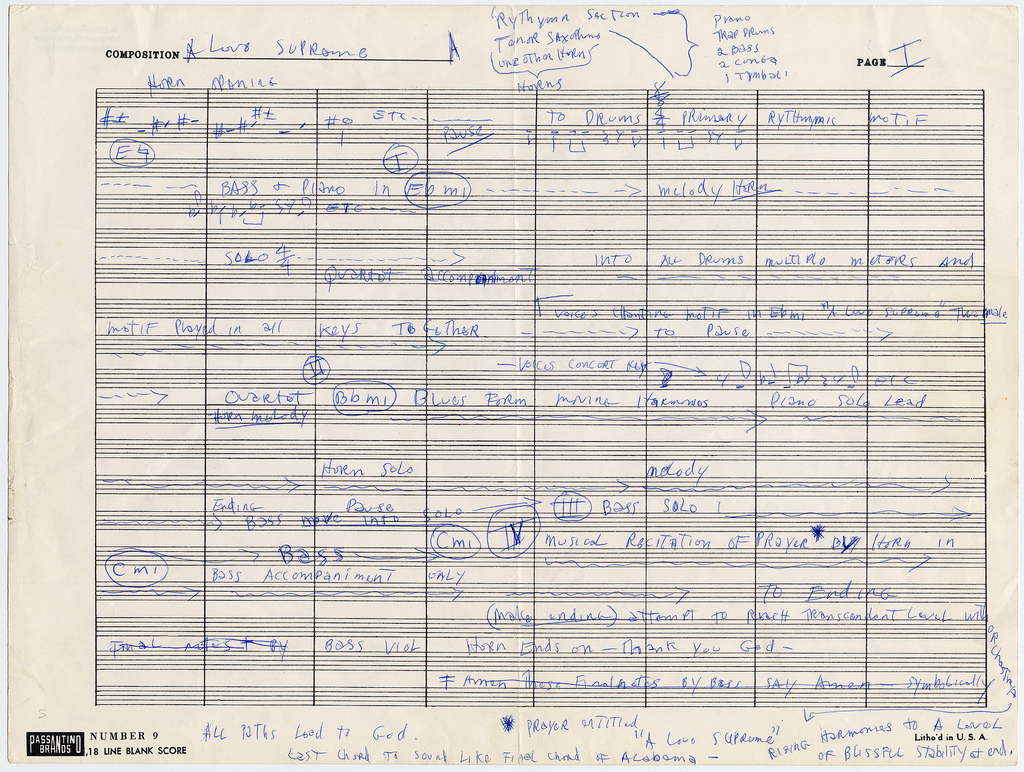

The manuscript of A Love Supreme, 1964.

Stein leads a group, with Fulgoni included, that has worked to make the Coltrane Home a public attraction. Visitors are not allowed inside at this point (though that hasn’t stopped travelers from finding their way and playing sax on the lawn, Stein said). But the plan is to restore everything to the way it was when the Coltranes lived there. The room upstairs will be a sanctuary. The ashram will be retrofitted. The recording studio in the basement will be able to power up and roll tape.

It’s a long way from realization yet, but Stein said he hopes the home can open sometime in 2017. The mold remediation is near complete, and a new roof has already been installed. An architecture group from Columbia University is studying bits of wall samples to date different layers of paint, so as to pinpoint the right one for the desired era. Varieties of vintage glass are being surveyed.

“One of the really important things in the world of historic preservation is windows, and that’s one of the battles we have to wrangle with,” Stein said. “New windows are very energy efficient. Double-pane, triple-pane, low-E—all this stuff is great. But those aren’t the windows that the Coltranes looked out onto the world from, so we have to get those windows back. That was a line in the sand.”

The ambitious plan also includes proposals for musical education programs around Dix Hills and an education center on the house grounds.

“Alice said she wanted [the rehabilitation] to be not just about the building itself,” explained Stein. “She said, This isn’t just about the home—it’s about getting people of all ages and backgrounds to participate in the making of music and the creative process, to engage them in the joy. That dramatically expanded the vision of what would otherwise just be a restoration project. The Coltranes were about using music as a force for good.”

Volunteer contractors have helped in the rebuilding so far, and the group behind the project is now looking to raise $2.5 million, through a combination of private donors and public grants. The board of the organization includes some notable names, including Ravi Coltrane and Japanese Coltrane scholar Yasuhiro Fujioka, as well as honorary members Carlos Santana, Tavis Smiley, and Cornel West.

But it’s mostly a local Long Island affair, with a team of volunteers—“It’s a consumptive part-time job,” Stein said of the staff—on a quixotic mission to make a plain suburban home as plain as it once was. Or not so plain, as the case may be.

The carpet in the master bedroom.

This article first appeared in the Norwegian jazz magazine Jazznytt.

Andy Battaglia is an arts writer in New York. His work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, The National, Frieze, The Wire, The New Yorker,and more. Find him here.