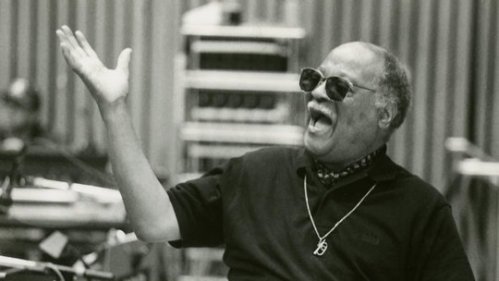

I was reluctant to watch the new documentary, KEEP ON KEEPIN' ON, about the relationship between aging jazz master Clark Terry (now 94) and his young protege Justin Kauflin (now 26). Years ago, Cee Tee told audiences — frequently and loudly — "The Golden Years SUCK!" and what I knew of his medical woes, diabetes culminating in loss of sight, and the amputation of both legs, had left me unwilling to watch a film chronicling the physical decline of a great artist.

I now know that this moving documentary is so much more than a chronicle of the physical breakdown of a once-vibrant man. I came away from the film uplifted by Clark's indomitable love and spiritual energy, a bubbling life-force that cannot be stifled.

But this is not only a film about Clark Terry. And although there is a good deal of rewarding archival footage (younger Clark with Ellington, Basie, and Quincy Jones) it is not a memorial to him.

Rather, it is about a mutual exchange between Terry and the young, inventive jazz pianist Kauflin who becomes Terry's student — but at the same time sustains the older man, energizes him, and since Terry was losing his sight, develops into a valuable guide into that other world. (Kauflin lost his sight completely at 11.)

Cee Tee is able to teach the younger man valuable life-lessons about more than music, but Justin returns the favor generously, becoming a son both Terry and his wife can nurture. The film deftly and tenderly chronicles their relationship, not neglecting the sorrows along the way: Terry has immense medical setbacks; Kauflin is a semi-finalist in the Thelonious Monk competition but other pianists make it to the finals.

At the end of this beautifully photographed and edited film, there have been triumphs. In Kauflin's case, he has impressed Dianne Reeves and Quincy Jones, so much so in the latter's case that Jones has featured the young musician at the Montreux Jazz Festival and has asked him to be part of his next CD. For Terry, the triumphs are enacted on a smaller scale but are no less important. He keeps on, and it is not simply a matter of not dying. In the last minutes of the film, we see him instructing a young saxophonist in how best to phrase a flurry of notes. We leave the film with faith in Terry as a beacon of love and music — and we know that the young men and women he has taught and inspired will go on to inspire generations not yet born.

The film is full of delights: Terry's instructing Kauflin in "old songs" such as BREEZE, talking with him about Ellington, and helping Kauflin become not only a better pianist but a more courageous young man. We see Terry's generous spirit and the loving relationship he and wife Gwen have and sustain, and we understand more about Clark because of brief interviews with Herbie Hancock, Jones, and even an archival clip from Miles Davis. The film also lets young Kauflin have his say, and he comes across as self-aware, charming, and gracious, very much aware of his debt to his mentor.

Because the film's director, Alan Hicks, was also a student of Terry's, the film is lit from within by a rare sensitivity. It does not view the world of jazz superficially and erroneously from the outside. The film never seems maudlin or overdone, and critical audiences searching for errors won't find them. And the musicians who praise Clark seem so fresh, their voices so authentic.

What any audience will find in this compact film (84 minutes) is love: passing generously between Cee Tee and his fellow musicians, to and from Justin, Gwen, and the characters who are fortunate to be in this aura. There's also Justin's frisky but loving guide dog, Candy (whose name provokes an impromptu Terry vocal on that Forties ballad).

The film offers a model for a sustaining spiritual exchange, where an Elder of the Tribe, honored and respected, has wisdom to pass on to the Youngbloods. And we can all learn from Terry. That Kauflin has done so with such easy openness is a testament to his heartfelt nature — Elders need Youngbloods to inspire. Hicks has returned his love to Terry through this film, which took five years to complete.

I urge you to seek out and watch KEEP ON KEEPIN' ON. As a document of affectionate mutual generosity and swinging music, it will inspire you. Here is the film's Facebook page, and here is a brief trailer.

Because for all its sad events, the film is light of heart, I have to conclude with something in that spirit. I now have a new catchphrase (although I might be reluctant to use it). Terry taught a very young Quincy Jones, who has never forgotten his mentor's the kindness. They greet each other with a trumpeters' in-joke: "Are your lips greasy?" meaning "Are you still playing? Are you still making the effort?" I'd like to see that cheerful phrase (puzzling to those not in the know) become part of any conversation.

May your happiness increase!