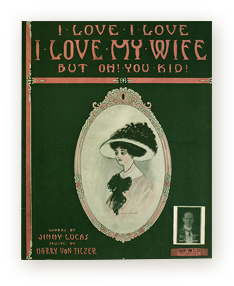

In the spring of 1909, American popular song got sexy. Of course, love and courtship, and by extension sex, had been Topic A in pop music for decades. But while songwriters had long trafficked in euphemisms and innuendo—coy talk of “sighing” and “spooning” beneath the old oak tree and by the light of the silvery moon—it was a 1909 hit by composer Harry Von Tilzer and lyricist Jimmy Lucas, “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!,” which opened Tin Pan Alley to brasher, bawdier, more raucously comic songs of lust.

In 2014, “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” is forgotten by all but a few antiquarians. It deserves better. It’s a landmark, worthy of a place in the pantheon alongside “Give My Regards to Broadway” (1904) and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” (1911)—and, for that matter, “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Rapper’s Delight.” Like “The Twist” and “Call Me Maybe,” it was a viral hit, inspiring hundreds of spinoffs and rippling through American culture for decades before dropping out of earshot. It was a succès de scandale, which brought roars from vaudeville audiences and censure from social reformers, with all sides agreeing that “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” had captured the zeitgeist, that it was a sign—the sound—of the times. It incited countless newspaper editorials, fulminating sermons by preachers, and at least one fatal shooting.

Today, to the extent that we think at all about the turn-of-the-century hit parade, we regard it as prehistoric: quaint old music, redolent of ill-tuned pianos and gas-lit Rialtos, that was swept aside by grittier sounds, by the triumphal rise of jazz and rock ’n’ roll. If we listen closely to “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” we may hear a surprising lesson: that the culture-quaking shocks, the salaciousness and transgression we associate with blues and jazz and rock and hip-hop, first arrived in American pop many years earlier. There is more than a nostalgia trip in this 105-year-old opéra bouffe about an adulterous husband and wife.

The saga of “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” began like many on Tin Pan Alley: with theft. In 1908, the Shapiro Music Company published “Oh, You Kid!,” by the songwriters Edgar Selden and Melville J. Gideon. “Oh, You Kid!” was standard fare, a typical comic-courtship song: a catchy trifle, carrying a whiff of sex, but moderate in temperature and tempo.

Oh, you kid! Oh, you kid!

Come now, say you’ll let me cuddle closer

Nod your head but don’t you answer “No sir”

Oh, you kid! Oh, you kid!

I mean every word I’ve ever told you

Kiss me quick or else I’ll have to scold you

Oh, you kid!

The appeal of “Oh, You Kid!” lay mainly in that slangy endearment, “kid.” Like another novel usage of the period, “baby,” “kid” held a hint of pillow-talk intimacy—a frisson that was enhanced by the threat to “scold” the kid who fails to deliver a quick kiss.

“Oh, You Kid!” was evidently a minor hit. (Just after the new year in 1909, the New York Star, a show business trade paper, reported that sales of the song’s sheet music had surpassed the 100,000 mark.) It certainly caught the attention of songwriters. In May 1909, Harry Armstrong and Billy Clark, a vaudeville duo that also wrote songs, borrowed the “Oh, You Kid!” refrain for a new number, “I Love My Wife; But, Oh, You Kid!,” about a henpecked husband who lusts after a lady seated next to him in a restaurant. Armstrong & Clark’s song had a plodding tune and an awkward lyric; it didn’t catch on. But it did its work, inspiring another song.

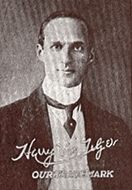

Copyright law had not yet caught up with the pop song business in 1909. Plagiarism was a thriving Tin Pan Alley institution; a pilfered song was, in the language of the trade, “a steal”—a fact of life in a cutthroat industry that thrived on trendiness and topicality, and held as an article of faith the belief that every hit could and should serve as a launching pad for dozens of light rewrites. The situation was exacerbated by the proximity of rival song publishing companies, which were clustered, in box-like offices, in the buildings that lined West 28th Street between Broadway and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan. In this cheek-by-jowl setting, new melodies could filter through walls and windows and be co-opted by competitors; songwriters threaded folded newspapers between piano strings to mute the instruments. The result was a tinkling, tinny piano sound, ringing out of the windows of song publishing firms, a din that earned the West 28th Street strip, and the song business at large, the moniker Tin Pan Alley. The nickname was bestowed by journalist Monroe Rosenfeld, who, according to legend, coined the term while interviewing Harry Von Tilzer at the songwriter’s office in 1900.

Courtesy of

Wikimedia Commons

Von Tilzer muted his upright piano to protect against song thieves; he was a charter member of the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers, the performance rights organization, founded in 1914, that brought a measure of law and order to the Wild West of pop music intellectual property. But that didn’t stop Von Tilzer from swiping a good idea when he heard one.On May 12, 1909, just nine days after Armstrong & Clark published “I Love My Wife; But, Oh, You Kid!,” Von Tilzer and Jimmy Lucas released their own variation. It was a heist and an upgrade, improving on the Armstrong & Clark original with a more winning melody, with sharper and racier lyrics, and with not one but three “I Loves” in the title.

Now Jonesy was a married man—oh yes, he was

Sweet girlie on the single plan—I guess she was

Jonesy stopped and spoke to girlie

Just as old friends often do

And he said, “I’m married but”

“That ‘but,’ my dear, means you”I love, I love, I love my wife—but oh, you kid!

For my dear wife I’d give my life—but oh, you kid!

Now wifey dear is good to me, a wrong she never did

I love, I love, I love my wife—but oh, you kid!

The success of Von Tilzer and Lucas’ “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” was in part a matter of the superior song craft. The lyric is cheeky; turn-of-the-century slang dictionaries suggest that I may not be wrong in detecting a saucy pun on the word “but” in the last line of the first verse. (“I’m married but/That‘but,’ my dear, means you.”) Von Tilzer’s fluency with hooks is on display, especially in the chorus, with its wide melodic leaps and that taunting singsong refrain, “Oh, you kid!”

What really set the song apart in 1909, though, was its tone: the relish with which extramarital shenanigans were depicted. For decades, popular songs about adultery had been Victorian morality plays—dolorous parlor ballads in 3/4 time, which promised that loneliness and ostracism awaited those who dared defile the marital bedchamber. Even comic songs had a strain of moralism: In Armstrong & Clark’s “I Love My Wife; But, Oh, You Kid!,” the husband with the wandering eye gets his comeuppance when, in the second verse, his wife turns up in the restaurant to drag him out the door. But in Von Tilzer and Lucas’ song, the flirting in verse one is apparently successful—and when the wife materializes in the second verse, she’s busy having her own fun, with a butcher:

Now Jonesy’s wife and butcher man each morn would chat

This butcher too was married but she didn’t mind that

And when poor Jonesy left the house each morning

They would sit and spoon

“Tell your tootsie who you love”

Then softly he would croon:

“I love, I love, I love my wife—but oh, you kid!”

What we have here, in other words, is a Progressive Era “O.P.P.”—a song that insists, as Irving Berlin put it a few years later in spiritually kindred number, “everybody’s doin’ it now.” How exactly Von Tilzer and Lucas’ song became a hit is uncertain. In 1909, the recording industry was still in its infancy, the popular music economy was fueled by sheet music sales, and hit songs were usually made in live performance, on the vaudeville circuit. The surest way for Tin Pan Alley song pluggers to turn a new number into a hit was to place it in the act of a prominent variety stage performer, a task usually accomplished by pressure or payola—by arm-twisting, horse-trading, and often enough, straight pay-for-play bribery. If all went well, the song would be added by a well-known singer and “go over” onstage; additional performers would make room for the number in their repertoires, and vaudeville touring troupes would take the tune from New York out across the country. Dance bands, restaurant orchestras, singing waiters, and street-corner buskers would likewise pick up the song; player-piano rolls would be recorded, and occasionally, singers would cut a wax cylinder or 78 RPM record. Eventually, a hit song would make the leap that music publishers really cared about, from the public to the private sphere: from the vaudeville proscenium to the sheet music stands of a million parlor room pianos.

Graphic by Slate

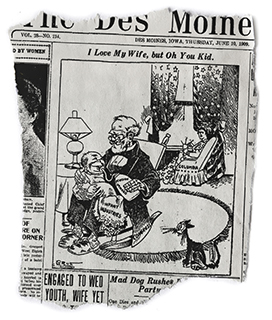

The performance provenance of “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” is unclear: I’ve found no evidence indicating when the song was introduced, or by whom. We can assume, though, that it was scooped up by several singers. Harry Von Tilzer was a reliable hitmaker; when a new Von Tilzer number was published, vaudevillians snapped to attention. In any event, the historical record is unambiguous about the song’s swift migration from New York to, as Von Tilzer and his Runyonesque Tin Pan Alley colleagues would have put it, the sticks. Less than a month after its publication, “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” had traveled as far west as Iowa: On June 10, the Des Moines News ran a front-page above-the-fold editorial cartoon about congressional spending that punned on the song’s title.

By the time spring turned to summer, “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” was inescapable. “In 1909, most of us gentlemen…were parroting ‘I love my wife, but oh, you kid!”’ wrote the Algonquin Round Table wit Franklin P. Adams in a 1938 New Yorker reminiscence. Gentlemen weren’t the only ones who succumbed. The song cut a wildfire path across popular culture. What survives today of the craze that one wag called “the ‘Oh, You Kid’ madness” is a cabinet packed with curiosities: one-reel motion pictures, studio photographs, neckties, pinback buttons, lapel pins, porcelain figurines,souvenir dishware, and hundreds of picture postcards, which savored the song’s naughtiness and foundfodder for lame jokes, silly wordplay, and racial and ethnic caricatures.

Like other pop culture catchphrases, from “Elementary, my dear Watson” to “Whoomp! There It Is,” the song’s slogan quickly became ubiquitous, seducing millions and annoying nearly as many. It was used in advertisements for everything from Broadway musicals to pretzels. It was translated by newspapers into Esperanto (“Ho! Vi kaprido!”). It was bellowed by a lovelorn Philadelphian as he leaped from a bridge into the Schuylkill River, attempting suicide. It brought scandal to a church in Geneva, Ill., when a prankster altered the hymnal, adding the line “but, oh, you kid!” to the lyrics of the devotional “I Love My God.” It wasgraffitied on a newlywed couple’s honeymoon cabin, next to another bawdy phrase, “Cum Rite Inn.”

A dispatch from New York published in the July 19, 1909, edition of the Walla Walla, Wash., Evening Statesman bemoaned the “damfoolishness” of the “Oh! You Kid!” phenomenon:

If anything was lacking—but there it isn’t—to prove that New York is the biggest yap town in the universe, and entitled to the appellation of the rube city, it could be found in the acceptance of such slang phrases as “Oh, you kid.” Meaningless jargon that it is, utterly bereft of any glimmer of common sense that would appeal to the intelligence lurking in the noodle of a new-born doodle-bug, the phrase has been taken up and perpetuated by millions of the human insects that have their burrows in the metropolis. On the streets one is greeted by hawkers offering for sale buttons bearing the idiotic refrain—buttons from which dangle rude caricatures of nude infants—and which are thrust into the faces of men and women alike with insulting repetitions of the phrase. Phonographs repeat the idiotic exclamation, and vaudeville performers inject it forcibly into their already wearisome dialogue.

The reach of “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” extended to the White House. At the Gridiron Club Dinner, the annual gala gathering of Washington elites attended in December 1909 by President William Howard Taft, the president was saluted in song: “We love, we love, we love Roosevelt—but oh, you Taft!” By the time the new year rolled around, “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” fatigue itself had become a cliché. (“Perhaps the worst thing 1909 has to answer for is the ‘Oh You, Kid!’ idiocy,” sighed the editorial page of the Arizona Silver Belt.) The Denver Post simply gave in, greeting 1910 with the inevitable “We loved the old year, but Oh, You Kid!”

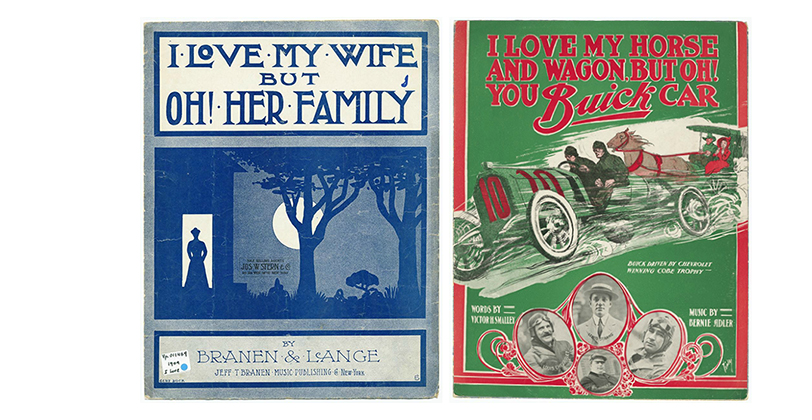

The epicenter of “oh, you kid!”-mania was Tin Pan Alley. Songwriters scrambled to capitalize on the big hit, pumping out parodies and rewrites: “I Love My Wife—But Oh! Her Family,” “I Love My Pipe—But Oh You Pippin!,” “I Love My Horse and Wagon—But Oh You Buick Car!,” and copious winking–and–nudgingvariations on the “kid” theme—tales of street corner pickups and illicit rendezvous.

Graphic by Slate

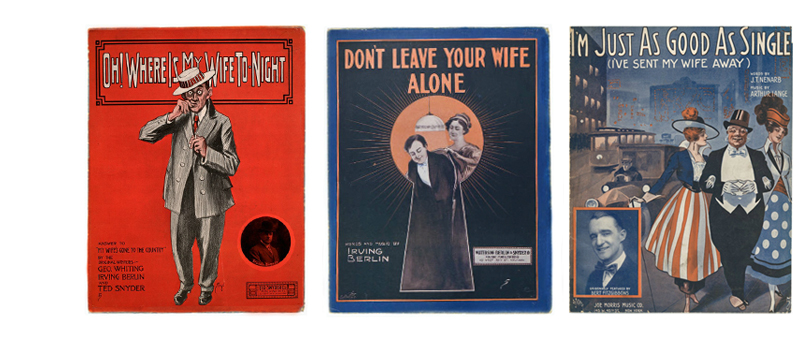

Meanwhile, song after song played adultery for laughs, with the body count of cuckolded husbands and abandoned wives piling high: “I Won’t Be Home ‘Till Late, Dear,” “She Borrowed My Only Husband (And Forgot to Bring Him Back),” “If You Talk in Your Sleep, Don’t Mention My Name,” “Oh! Where Is My Wife To-Night,” “I Trust My Husband Anywhere But I Like to Stick Around,” “I Can Dance With Everybody but My Wife,” “Don’t Leave Your Wife Alone,” “I’m Just as Good as Single (I’ve Sent My Wife Away),” “You for Me When Your Wife’s Away,” “I’m Glad My Wife’s in Europe,” “Everything’s at Home Except Your Wife.”

Graphic by Slate

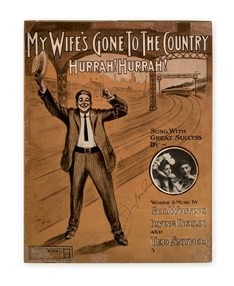

The most successful copycat song, “My Wife’s Gone to the Country! Hurrah! Hurrah!,” was the first hit by 21-year-old Irving Berlin. Berlin’s song was a pop culture sensation in its own right, but its chorus made no secret of the debt to “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!”

My wife’s gone to the country, hurray! hurray!

She thought it best

“I need the rest”

That’s why she went away

She took the children with her, hurray! hurray!

I love my wife, but oh, you kid!

My wife’s gone away

These spinoffs date from the months immediately following the publication of “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” But the original had a long cultural shelf life. In The American Language (1921), H.L. Mencken complained about the banality of the phrase “I love my wife, but oh you kid!,” which he nonetheless included in a list of “current phrases and proverbs … that display the national talent for extravagant and pungent humor.” “I love my wife, but oh you kid!” was a favorite quip of Groucho Marx, who used it for years in comedy routines, and as a tagline when he signed autographs. The phrase pops up in John Dos Passos’ The 42nd Parallel (1930), in William Faulkner’s The Town (1957), in Joseph Heller’sSomething Happened (1974). Delmore Schwartz, in his 1948 novella The World Is a Wedding, puts the words “I love my wife, but oh you id,” in the mouth of a character who, Schwartz writes, “had studied Freud and Tin Pan Alley.”

For decades, musical revivalists returned to Von Tilzer and Lucas’ hit for nostalgic titillation—for a dose of raunchiness in period dress. The 1946 MGM movie musical The Harvey Girls, a turn-of-the-century period piece starring Judy Garland, featured a new Harry Warren–Johnny Mercer song, “Oh, You Kid,” performed by Angela Lansbury as a high-kicking burlesque number. “Oh you kid, does wifey keep you hid?/I don’t know if she does, but she’d be wiser if she did,” Lansbury sang.

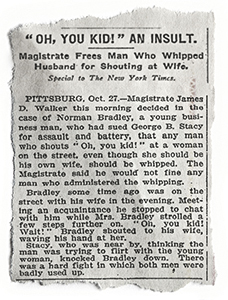

To filmgoers in 1946, the turn-of-the-century bawdiness revisited in “Oh, You Kid!” must have seemed quaint. In 1909, Von Tilzer and Lucas’ song was anything but. “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” played sexual brazenness for laughs, but to many it was an affront—a fire-in-a-crowded-theater provocation that crossed the boundary of decency. The song was a culture war flashpoint, the subject of legal imbroglios, and, sometimes, an inciter of violence. A Missouri farmer who sent a young woman a postcard bearing the legend “I Love My Wife, But Oh You Kid!” was hauled into United States District Court in Jefferson City, threatened with five years imprisonment, and given a stiff fine for the crime of “sending improper matter through the mails.” In Los Angeles, a “petite and pretty” woman, Marie Durfee, assaulted a man after he greeted her on the street with the song’s catchphrase. A police court judge sided with Durfee,ruling: “The salutation, ‘Oh, you kid!’ is a disturbance of the peace and is punishable by ninety days’ imprisonment in the city jail.”

Graphic by Slate

Other jurists were more severe. The Oct. 28, 1909, edition of the New York Timesnoted a bizarre ruling by a court in Pittsburgh: “Any man who shouts ‘Oh, you kid!’ at a woman on the street, even though she should be his own wife, should be whipped. The Magistrate said he would not fine any man who administered the whipping.” An editorial writer in Arizona went further: “The man who without cause or reason, says ‘I love my wife, but oh you kid!’ would not wear his button long, for the fool killer would start for him and mercifully end his existence.” That scenario was not, it turned out, farfetched. In October 1910, in Atlanta, a man named N.H. Bassett was shot by George Lambert, a railway company executive, after Bassett approached Lambert’s wife on the street crying, “Oh, you kid!” “It is believed Bassett will die,” wire services blithely reported. “Lambert surrendered, but was at once released.”

The furor over “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!,” like the song itself, was definitively a thing of its time. Behind the sidewalk confrontations and draconian legal rulings we can perceive the anxieties of that post-Victorian moment: concerns about coarsening manners, about changing courtship rites, about the threat posed by modernity to the 19th-century ideal of “pure womanhood.” Traditionalists’ fears were heightened by the women’s suffrage movement, which held the promise of political enfranchisement and further freedoms, including sexual ones. That prospect was celebrated by popular songwriters, who indulged their taste for egalitarian erotic adventure in romps like “I Love My Husband, But—Oh, You Henry!” and “I Love My Steady, But I’m Crazy for My Once in a While.”

Graphic by Slate

Blame for the erosion of traditional values was often placed on mass culture, in particular on popular music. The criticism had a racialist-tinge: Pop’s polyglot sound was scorned as a social contagion, a toxic blend of black ragtime’s “jungle rhythms” and the “low-class melodies” churned out by Tin Pan Alley’s “Hebrew song mills.” But the fears always circled back to women and sex. An article in the April 1910 issue of the American Magazine decried “The Decay of Vaudeville”:

The only limit is what the police will allow, and the police apparently draw the line only at indecent physical exhibitions, and not always there. The far more pernicious evil of suggestive songs and lewd, lascivious jests goes quite unheeded by the authorities. It is a fact that if your wife or your daughter goes to a vaudeville theatre at the present time the chances are at least seventy-five in a hundred that she will hear some jest or some song that reeks of the barroom or worse.

One “suggestive song” in particular drew the ire of pundits, social reformers, and clergy. Wilbur F. Crafts, a Methodist minister and the head of the Washington, D.C.–based National Reform Bureau, decried “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” in newspaper interviews. “Use of the expression ‘I love my wife, but, oh you kid,’ greatly injures people’s morals,” Crafts said. “People laugh when I say that, but it’s true just the same.” A 1909 essay in the magazine Physical Culture echoed the sentiment:

One of the most amazing exemplifications of the morals of mankind, and womankind also, has been indicated in the popularity of a sort of ribald song which very clearly portrays an unfaithful husband. The most popular phrase in this song is “I love my wife, but oh you kid.” Wherever this song is sung it is hilariously applauded. The singer is always careful to so modulate his voice as to make his meaning very clear. … National life depends on moral life. Loose morals, debased principles, degeneracy, they mean a gradual destruction of mankind. … “I love my wife, but oh you kid.” Is there anything amusing in the thought conveyed?

Courtesy of Library of Congress

The song’s most prominent opponent was Billy Sunday, the evangelical preacher who commanded an audience of millions in the first decades of the century. In a 1911 sermon, Sunday rained fire and brimstone on pop music: “In times past, popular plays and their songs used to glorify the marriage relation. Now we hear such songs in the theater as ‘My Wife Has Gone to the Country, Hurray! Hurray!’ and ‘I Love My Wife, But Oh You Kid!’ These are things of the devil, things driving audiences to sin and hell.” Tin Pan Alley, of course, had an answer for the evangelist: “I Love My Billy Sunday, But Oh You Saturday Night.”

Sunday wasn’t exactly wrong, though. Deglorifying “the marriage relation” wasn’t just fun sport and big business on Tin Pan Alley. It was cutting edge. “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” and the cheating anthems that followed it marked an aesthetic shift. In the past, songwriters had channeled ribaldry into minstrelsy, displacing sexual misbehavior onto ethnic characters, especially blacks, as in Harry Von Tilzer’s 1899 coon song hit, “I’d Leave Ma Happy Home for You.” Songs like “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” took a different tack: They embraced mild ragtime syncopation but were performed by vaudevillians without dialect, in the voices of “normal” bourgeois white Protestant Americans. These songs were doubly modern, bringing new forthrightness about sex—it was a thing, it seemed, that even respectable white people did, for fun—while gentrifying and deracinating ragtime: recasting the expressive vocals and jaunty rhythms, previously reserved for blackface songs, as vernacular Yankee Doodle American pop. Consider “My Husband’s in the City,” an answer to Berlin’s “My Wife’s Gone to the Country,” as drawled in a 1910 recording by Sophie Tucker.

When summer comes we go away

To mountains or seashore

I can’t take hubby with me, poor boy

He must mind the store

You bet he’s having one good time

Although he writes he’s blue

But he ain’t got a thing on me

I have a good time, too

Oh! My husband’s in the city

’Bout a hundred miles away

He thinks for him I’m pining

“Fading away”

So he comes out every Friday

For what, I do not know

But he only stays ’till Sunday

Hurray! Hurrah! Hurrow!

Songs like “My Husband’s in the City” are a reminder that popular music in this period aimed for the funny bone with an intensity that it hadn’t before, and hasn’t since. The jokes were in part a response to the sentimentality of 19th-century pop, which was dominated by florid love ballads and tear-jerkers. Curiously, one of the star practitioners of the old style was Harry Von Tilzer. In the decade prior to the publication of “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!,” Von Tilzer had established himself as the Alley’s marquee songwriter-mogul by specializing in schlock.

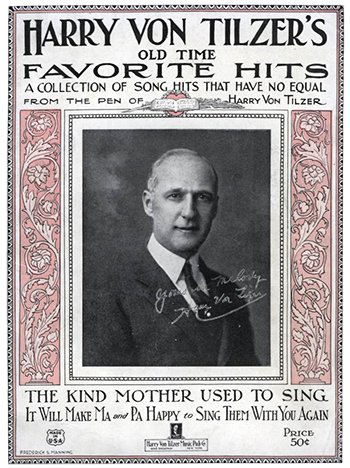

Harry Von Tilzer is one of the more remarkable figures in the history of American song. He was born Aaron Gumbinsky, in 1872, in Detroit, to German-Jewish immigrant parents. When he was 14, he ran away from home to join the Cole Bros. Circus, where he worked as a singer and an acrobat. A year later, he relocated to Chicago, where he took a job playing piano and singing in a variety theater troupe. He began dabbling in songwriting, published his first number in 1892, and relocated to New York to pursue the career. (He was followed to Tin Pan Alley by his younger brother, Albert, who eventually earned fame as the composer of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.”) Aaron had earlier changed his name to Harry Gumm, but in New York he changed it again, adding an aristocratic “Von” to his mother’s maiden name. His breakthrough came in 1898 with “My Old New Hampshire Home,” a sentimental ballad lifted out of the goop by Von Tilzer’s stirring tune. The song’s sheet music sold 2 million copies—the first in a long string of multimillion-selling hits.

Von Tilzer’s biography, in other words, traces a familiar path: From child of the Jewish ghetto to bootstrapping showbiz tyro to autodidact all-American hit-maker. It’s the heroic trajectory we associate with Irving Berlin, and although Berlin always claimed Stephen Foster as his muse, Von Tilzer was his real model—right down to the fancy adopted “German” surname. Berlin’s first paying Tin Pan Alley gig, when he was still Izzy Baline, was as a guerrilla song plugger, or “boomer,” for the Harry Von Tilzer Music Publishing Co. (It was his job to stir up enthusiasm for newly published Von Tilzer numbers by shouting for encores from the vaudeville cheap seats.) Not only was Berlin’s debut hit an “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” rewrite, the song that made Berlin’s career, the 1911 smash “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” was a sequel to Von Tilzer’s hit coon song, “Alexander, Don’t You Love Your Baby No More” (1904), and Berlin’s great 1924 torch ballad “All Alone” (“All alone/By the telephone/Waiting for a ring …”) was transparently based on Von Tilzer’s 1911 “telephone song” of the same title.

It was Von Tilzer’s approach to songwriting, his productivity and populism, which really blazed the trail for Berlin. Von Tilzer was the consummate Tin Pan Alley workhorse. He cranked out thousands of songs, trying his hand at every imaginable genre and sub-genre, while heeding the slightest shifts in the variable winds of public taste. He composed love songs and rags and patriotic tunes; he had hits with blackface numbersand German dialect songs. He put out topical songs about Ouija boards, Liberty Bonds, prohibition, and the discovery of Tutankhamen’s tomb. He spurred dance crazes with “The Cubanola Glide” (1910) and “The Bunny Hug” (1912). His 1905 ballad “Wait ’Till the Sun Shines, Nellie” is still the unofficial theme song of the New York Stock Exchange.

Von Tilzer wrote lyrics as well as music, although he rarely took credit for them. In fact, in a 1943 lawsuit, Von Tilzer claimed that he, not Jimmy Lucas, had written the words to “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!”: that he’d agreed to give away the lyric-writing credit because Lucas had suggested the title of the song and had promised to plug it. (This kind of transactional gifting of songwriting credits was a common practice on Tin Pan Alley.) Whether or not we take Von Tilzer at his word and regard “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” as his song, music and lyrics, it is an exemplary Harry Von Tilzer song—because of its catchiness and appeal, certainly, and because of its uncanny good timing, its arrival at just the right moment to satisfy a public eager for more piquantly spiced hits. That skill for zeroing in on the next big thing carried over to Von Tilzer’s role as a publishing tycoon and talent scout. A decade after giving Irving Berlin his start, Von Tilzer published the first song by 17-year-old George Gershwin, an inauspicious novelty piece called “When You Want ’Em, You Can’t Get ’Em, When You’ve Got ’Em, You Don’t Want ’Em” (1916).

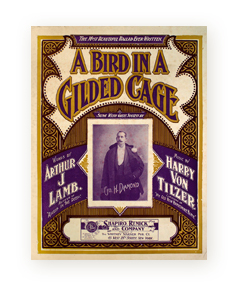

Von Tilzer was most famous for the ballads he composed in the 1890s and first years of the new century. The songwriter himself was unsentimental and ironic, but he had a knack for the kind of music, lavishly drizzled with schmaltz, that was feasted on by late-Victorian audiences: extravagant chromaticism bolstering lyrics about roses in bloom and sweethearts in the gloaming and old folks at home, and morbidly moralistic stories of dead babies, sainted mothers, and ruined womanhood. The biggest blockbuster of Von Tilzer’s career was the tremulous “A Bird in a Gilded Cage” (1900), which wagged a finger at a pretty girl stuck in a marriage to an old coot.

She’s only a bird in a gilded cage

A beautiful sight to see

You may think she’s happy and free from care

She’s not, though she seems to be

’Tis sad when you think of her wasted life

For youth cannot mate with age

And her beauty was sold

For an old man’s gold

She’s a bird in a gilded cage

If the sobs in this definitive turn-of-the-century “sob ballad” sound like they’re laid on extra-thick—they are. “A Bird in a Gilded Cage” began its life as a parody: Von Tilzer composed the music on a dare, when the lyricist Arthur Lamb challenged him to come up with a melody that would befit his preposterously soppy verses. The musicologist Jon W. Finson has written of “A Bird in a Gilded Cage”: “The whole song has an ironic quality to its melodrama, as if the author’s manipulation of sentiment were meant to be obvious. Von Tilzer overdoes the chromatic interludes between phrases, making a caricature of the period cliché in which imported cadences supported harmonies by descending a half step.”

The mischievousness of this stunt says a lot about Von Tilzer, and it sheds light on “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!,” which was often performed as a parody of Victorian ballad style. Listen to the hammy rendition of the song’s chorus recorded in 1909 by vocalist Arthur Collins. Collins lampoons parlor ballad waltzes, lustily rolling his R’s, quavering histrionically, and rising to a mock-operatic crescendos.

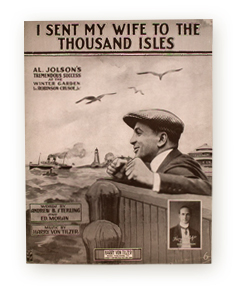

Vocal burlesques of this sort were common in the songs of the period, particularly in the adultery-themed songs that followed “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” A textbook case is another Von Tilzer number, “I Sent My Wife to the Thousand Isles” (1916), sung by Al Jolson in a rollicking travesty of light opera vocal style.

Just think when I get home tonight

There’ll be no wifey there

And right across the table

I will see a vacant chair

I love my wife, I love my wife

I love her more each day

I love my wife, I love my wife

Because she’s far away

What we are hearing in these send-ups is not just a joke about genres. It’s the sound of a generation gap opening: the brusque changing of the musical guard that takes place every couple of decades, when the young toss their parents’ soundtracks on the dung heap. In the ’50s and ’60s, Frank Sinatra and Patti Page were elbowed aside in favor of R&B and rock ’n’ roll. In the ’80s and ’90s, the children of baby boomers ditched rock for hip-hop. Thus “Let’s Make a Rag of the Old Oaken Bucket” (1911), which remade the 19th-century parlor room standard “The Old Oaken Bucket,” a maudlin ballad of childhood and old homestead nostalgia, as sex-soaked 20th-century ragtime: “Let’s make a rag of the old oaken bucket/Syncopate that melody/Let’s hug and squeeze while the keys nip and tuck it.” The next rhyme wasn’t, as in the dirty old limerick, “Nantucket”—but it may as well have been.

The standard historical narrative treats the 1950s as the dawn of popular music as we know it: the moment when the sex simmering beneath the surface bubbled to the top, when teenagers stampeded to dance floors, when rock ’n’ roll cracked open a gulf between the generations, never again to be bridged. But ’50s sock-hoppers were merely restaging scenes that had played out decades before. At the turn of the century, dance halls teemed with hormonal youth. From Dance Hall to White Slavery: The World’s Greatest Tragedy (1912), a tract about the evils of social dancing, noted with alarm that “an evening’s average of 86,000 young people attend the dance halls of Chicago,” where they “danced to the suggestive music of the cheap orchestras”—to Tin Pan Alley’s endless supply of “new and more suggestive” songs.

Ragtime’s slaves-to-the-rhythm weren’t just figments of Billy Sunday’s fevered imagination—and “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” wasn’t just a novelty ditty. It was, like the other hits of its era, a generational marker, an anthem of changing times and freedom and youth. The old songs sound goofy to us, but a hundred years ago they carried a teenybopper throb and the impish menace of punk rock.

Rifling the “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” scrapbook, we catch some intriguing glimpses of that young audience. The song was big on campus: The phrase “oh, you kid!” was banned at Yale, and Princeton University was scandalized when it awoke one morning in December 1909 to find those words slapped in bright red paint on the walls of the theological seminary’s chapel.

My favorite “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife—But Oh! You Kid!” artifact—the most alluring and mysterious one I’ve run across—is a photograph that I bought several years ago on eBay. Dated 1909, the snapshot captures four young people, apparently in their late teens or early 20s, sitting arm in arm on what looks like the lawn of a large house. They are pointing the soles of their eight shoes towards the camera, with a letter painted on each to spell out—what else?—OH YOU KID.

Am I the only one who finds this image eerily familiar? Am I wrong to imagine that we are looking at a turn-of-the-century version of the mods, the Deadheads, the breakdance crew? Who could doubt that it was these four, or their spiritual cousins, who defaced the seminary chapel at Princeton? And who can deny the rock-star charisma of the young woman second from the left, with her scarf knotted like a necktie, and a glower worthy of Chrissie Hynde? Her gaze, implacable and sphinxlike, feels like a taunt—a reminder of how little we know, how much we’ve forgotten, about our musical past. But there’s at least one clear message in that hard, cool stare: In 1909, as in 1966, as in 2013, the kids were alright.

Top Comment

I love my content-free Slate clickbait, but oh, you Jody Rosen! More…

-Draugr

57 CommentsJoin In